Phytochemical Screening and in vitro Evaluation of the Thrombolytic Activity of Chenopodium album L. Leaves

| Received 13 Dec, 2022 |

Accepted 26 Mar, 2023 |

Published 07 Jun, 2023 |

Background and Objective: Chenopodium album L. (Family: Amaranthaceae) is well-known for its nutritive and pharmacological values. Its leaves are used as a vegetable and recommended as a dietary inclusion for persons suffering from heart disease. Thrombus is the major cause behind the occurrence of cardiovascular diseases (CVD) and therefore, the objective of this paper was to evaluate the in vitro thrombolytic potential of its leaves. Materials and Methods: Leaves of C. album were collected from Udaipur, Rajasthan, dried and powdered. It is methanolic (ME-I and ME-II) and aqueous extracts were prepared. Besides, qualitative assessment of phytochemicals and in vitro clot lysis potential of its leaves in comparison with the positive control (streptokinase) and negative control (distilled water) was evaluated. Blood lipid fractions such as serum triglycerides (TG), total cholesterol (TC), Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol (LDL-C) and Non-High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol (Non-HDL-C) were estimated for finding out their correlation with thrombolytic activity. Results: Preliminary qualitative phytochemical analysis has shown the presence of flavanoids, terpenoids, steroids, phenols, tannin, saponin, cardiac glycosides, carbohydrates and amino acids and the absence of phlobatannins. A statistically significant (p<0.001) in vitroclot lysis activity of 39.70±0.99% was exhibited by methanolic extract of leaves as compared to streptokinase having 55.20±1.50% and distilled water having 3.62±0.30% clot lysis (n = 10). Notably, a moderate positive correlation between thrombolytic activity and total cholesterol, triglycerides and non-high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol was observed. Conclusion: The present study has first time demonstrated the significant in vitro thrombolytic potential of leaves of C. album. However, in vivo studies on a larger number of subjects along with the identification and isolation of phytochemicals responsible for thrombolysis are required.

| Copyright © 2023 Kunwar et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |

INTRODUCTION

Thrombus formation is the main culprit behind cardiovascular diseases (CVD) and mortality. The formation of blood clots (thrombus) occurs due to failure of the homeostasis process in the circulatory system which has serious consequences such as vascular blockage. Myocardial and cerebral infarction are often fatal outcomes of atherothrombotic disorders1. Lipids and lipoprotein particles also play an important role in the pathology of CVD by influencing inflammatory processes as well as the function of leukocytes and vascular and cardiac cells2. Blood stack occurs as a result of a series of sequential events, the final step in this process is the formation of thrombin, in which the soluble fibrinogen converts to insoluble fibrin3. To dissolve this thrombus, various thrombolytic agents such as tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), urokinase (UK), streptokinase (SK) and others are being used worldwide4. Due to their lower cost than t-PA, SK and UK are frequently utilized for thrombolysis, nonetheless, their use is linked to an increased risk of bleeding and allergic reactions1. To find a safe and effective thrombolytic agent, several research studies have been conducted worldwide on medicinal herbs and natural resources that have effective anti-thrombotic activity5. Plant-based herbal drug formulations have demonstrated that medicinal plants can be a good source of new therapeutic remedies for various clot-related disorders6.

Chenopodium album L. (Family: Amaranthaceae) is a small, herbaceous plant, known as Lamb’s quarter, Pigweed, Bethu sag, Beto, Bathua, Parupukkirai and Pappukura etc. in different languages. It is majorly distributed in South East Asia and found in the wild as well as cultivated throughout India up to an altitude of 4000 ft. Its leafy shoots are consumed as a vegetable7-9. In traditional medicine, it is used for the treatment of several human ailments such as asthma, back pain, cardiac disease, diarrhea, intestinal worms, jaundice, skin eruption, sprain, indigestion, seminal weakness, swollen gum, stomach pain, piles and wound etc.10-12. Many pharmacological activities have also been reported from the plant such as anticancer, analgesic, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antidiabetic, antiulcer, hepatoprotective, anthelmintic, contraceptive, antinociceptive, anti-diarrheal and immunomodulatory13,14.

Researcher has recommended many medicinal herbs and spices for treatment of heart disease15 as well as the therapeutic use of many vegetables as a dietary inclusion for persons recovering from heart disease and C. album is one of them. In view of all this, in the present study, for the first time, leaves extract of Chenopodium album was evaluated to find out it’s in vitro thrombolytic potential and further, its correlation with various blood lipid fractions such as serum total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol (LDL-C) and Non-High Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol (Non-HDL-C) was also assessed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Collection and preparation of plant material: Leaves of C. album were collected from an open farm at Shobhagpura, Udaipur, Rajasthan and identified with the help of flora of Rajasthan7. A voucher specimen of the plant was preserved at Herbarium, Department of Botany, Govt. Meera Girls’ College, Udaipur, Rajasthan, India and authenticated from Botanical Survey of India (BSI), AZRC situated at Jodhpur District in Rajasthan (BSI/AZRC/I.12012/Tech./2020-21-(Pl.Id.)/424, dated 08/02/2021, Sl. No. 2). Leaves of the plant were dried on the room temperature in shade and powdered. The study was executed during the period between August, 2020 to October, 2022.

Extraction details

Preparation of methanolic extracts16: Methanolic extract-I (ME-I) was prepared for preliminary qualitative phytochemical analysis by soaking 5 g dried powder in 50 mL methanol at room temperature and filtered after 24 hrs. This was repeated three times with 50 mL methanol. Methanolic extract-II (ME-II) was prepared for evaluation of in vitro thrombolysis by soaking 100 g dried powder in 500 mL of methanol for 8 days with occasional stirring and filtering. The filtrate was evaporated at a temperature of 40°C in a boiling water bath and then stored in the refrigerator.

Preparation of aqueous extract: Preliminary qualitative assessment of certain phytochemicals was done using freshly prepared aqueous extract by soaking 400 mg dried powder in 20 mL of distilled water, boiling for 20 min and then filtering.

Phytochemical analysis: The standard methodology was employed to detect the presence or absence of amino acids, carbohydrates, steroids, terpenoids, phenols, cardiac glycosides, flavanoids, phlobatannins, tannins and saponins in the leaves of C. album16-18.

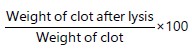

Evaluation of in vitro thrombolytic activity: Approval from the institutional ethical committee was obtained (Ref.PMU/PMCH/IEC/2019, dated 26.12.2019) and after informed consent, in vitro thrombolytic activity of ME-II was evaluated in the blood samples (10 mL each) of ten healthy volunteers. Healthy individuals who were not taking any drugs were included in the study. The experiment was carried out in triplicate. The methodology demonstrated by Prasad et al.19 was used to assess the in vitro clot lysis potential of leaves of C. album. Streptokinase (SK) was used as a positive control by dissolving lyophilized SK of 15,00,000 IU in 5 mL of sterile distilled water (STPase manufactured by Cadila Pharmaceuticals, Ahmedabad, India) out of which 100 μL (30,000 IU) was used for the test. Distilled water was used as a negative control. Initially, 20 sterile micro-centrifuge tubes were weighed. Then after, 500 μL of the blood was added to each tube and the tubes were kept in an incubator for 45 min at 37°C temperature. After the clot formation, serum was removed after centrifugation at 2000 rpm for 10 min and the weight of the clot was obtained by subtracting the weight of the tube from the weight of the tube with the clot. Then after, 100 μL of ME-II, sterile distilled water and SK were added to the tubes and kept at 37°C for 90 min. The impact of clot lysis was observed by removing the fluid and re-weighing of tubes to find out the weight of the clot after lysis. Percent clot lysis was determined as:

|

Estimation of blood lipids: Lipid fractions such as serum TC20 and TG21 were measured using standard enzymatic kits (Reckon Diagnostics P. Ltd., Baroda, India). Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol (LDL-C) was calculated by the Friedwald et al.22 formula as follows:

Non-High Density Lipoprotein-Cholesterol (Non-HDL-C) was calculated as follows23:

Statistical analysis: Results of in vitro thrombolytic activity were expressed as Mean±Standard Error of the Mean (SEM) for three replicates. Student’s paired t-test was used to check statistical comparisons by Microsoft Excel software (2010). Results were considered to be significant when the p-value was <0.01. The correlation between the blood lipids and clot lysis activity was assessed using Microsoft Excel (2010) at a significance level of 0.05 (p<0.05).

RESULTS

Qualitative phytochemical analysis: The preliminary phytochemical analysis has shown the presence of carbohydrates, amino acids, flavanoids, phenols, tannin, terpenoids, steroids, saponins and cardiac glycosides and the absence of phlobatannin in the leaves of C. album as shown in Table 1.

In vitro thrombolytic activity: The significant (p<0.001) in vitro clot lysis (39.70±0.99%) of ME-II as compared to SK (55.20±1.50%) and distilled water (3.62±0.30%) was observed as shown in Table 2.

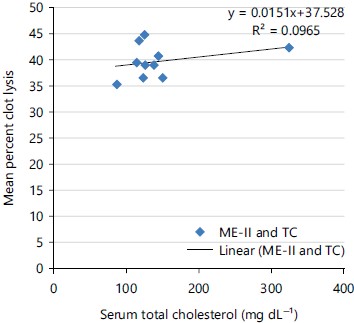

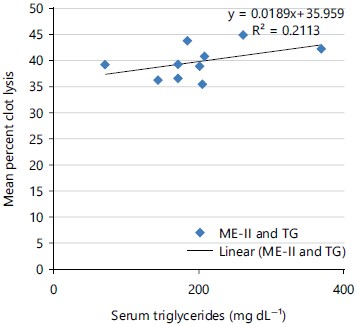

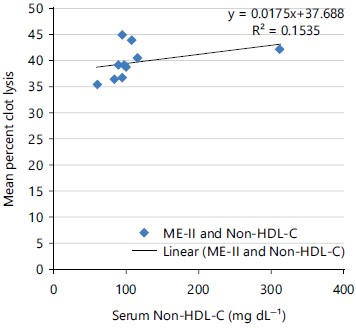

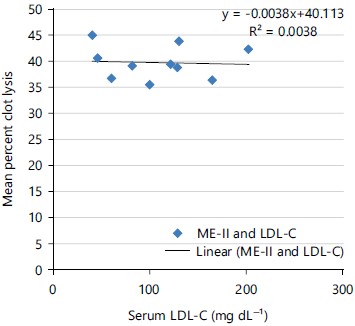

Correlation analysis between blood lipids and thrombolytic activity: A moderate positive correlation was observed between thrombolytic activity of C. album leaves and serum TC (Fig. 1), TG (Fig. 2) and non-HDL-C (Fig. 3) and a negative correlation was observed with LDL-C (Fig. 4). However, the correlation results were statistically not significant.

| Table 1: | Qualitative preliminary phytochemical analysis of leaves of Chenopodium album | |||

| Phytochemical | Chenopodium album leaves |

| Carbohydrate | + |

| Amino acid | + |

| Saponin | + |

| Flavanoid | + |

| Phenol | + |

| Tannin | + |

| Phlobatannin | - |

| Terpenoid | + |

| Cardiac glycoside | + |

| Steroid | + |

| +: Present and -: Absent | |

| Table 2: | In vitro percent clot lysis activity of methanolic extract of C. album leaves (ME-II) | |||

| Plant extract (ME-II)/control (100 μL) | Percentage of clot lysis (Mean±SE) |

| Methanolic extract (1 mg mL–1) | 39.70±0.99a,b |

| Distilled water | 3.62±0.30b,c |

| Streptokinase (30000 IU) | 55.20±1.50a,c |

| p-values: ap<0.001 ME-II as compared with streptokinase, bp<0.001 ME-II as compared with distilled water and cp<0.001 distilled water as compared with streptokinase | |

|

|

|

|

DISCUSSION

In the present study, leaves of C. album have also shown statistically significant in vitro thrombolytic potential of 39.70±0.99% as compared with both positive and negative control (Table 2). In addition to this, the presence of therapeutic secondary metabolites such as cardiac glycosides, flavonoids, phenols, steroids, terpenoids, saponins and tannins in its leaves, is an important finding (Table 1).

For the prevention and treatment of various chronic diseases use of natural foods or nutraceuticals is considered to be very beneficial. In traditional medicine, several food plants are recommended to treat various ailments but their systematic scientific validation studies are the need of the hour24. In this regard, the current scientific investigation on an edible plant C. album is noteworthy.

Thrombolysis is an important process in dissolving the blood clot and thus, helpful in maintaining the patency of blood vessels5,25. Several plants have been screened for in vitro thrombolytic potential. For example, 43.94±0.62% clot lysis was shown by chloroform extract of Centella asiatica24, 37.17% by ethanolic extract of Ficus palmata26, 41.40±2.02 and 20.52±1.51% clot lysis by leaves and flowers of Moringa oleifera, respectively16, 33.17% by roots of Phyllanthus fraternus27 etc. In this context, 39.7% of thrombolysis activity as shown by C. album is an important observation of the current study.

The presence of phytochemicals imparts therapeutic potential in plants. For example, cardiac glycosides are used as a treatment for heart problems and have also been used as heart tonics, diuretics and emetics in folk medicine for centuries28. Similarly, flavonoids also play an important role in the prevention of CVD, owing to their antiatherogenic, antithrombotic and antioxidant properties29. The protective role of phenolic compounds against atherothrombosis is also shown by their antiplatelet, anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities30. Leaves of C. album also possess antioxidant31 and anti-inflammatory activities32 along with a high amount of total polyphenols and flavanoids (550 mg gallic acid/100 g dry weight and 1880 mg rutin/100 g dry weight), respectively33. Phenolic compounds and flavonoids with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties have also been shown to possess anticoagulant properties34. In this regard, the presence of rutin, cinnamic acid, gallocatechin, catechin, coumaric acid, ferulic acid, sinapic acid, caffeic acid and chlorogenic acid along with other phytochemicals for example, β-carotene, lupeol, β-sitosterol, ascorbic acid, etc.13,35-37 in C. album leaves, could be responsible for its anti-thrombotic potential. However, the quantitative estimation of these potentially heart-beneficial phytochemicals should be carried out along with the isolation of specific anti-thrombotic molecules from its leaves.

Abnormal lipid profile and coagulation parameters, high blood sugar, obesity, etc. are the major reasons behind the development of CVD38. The link between cholesterol levels and the occurrence of heart attacks has been shown in scientific studies2. Methanolic extract of C. album has shown a significant reduction in lipid parameters such as total cholesterol, plasma triglycerides, LDL-C, atherosclerosis Index and suggesting that its consumption may reduce the risk of CVD39. Besides the hypolipidemic activity of C. album, the moderate positive correlation between TC, TG and Non-HDL-C (Fig. 1-3) and the thrombolytic activity as shown in this study indicates better thrombolytic protection by C. album leaves even in the conditions of elevated lipids. Based on this, it could be recommended to be included in the diets of persons suffering from heart disease as also suggested by researcher15.

The limitation of this study is that it is conducted in vitro with a small number of blood samples and with a specific concentration. In the future, a study with a large number of samples and with different concentrations of plant extract could be carried out. Moreover, in vivo, studies in doses equivalent to its natural form could be conducted. The plant is eaten in various recipes such as vegetables, parantha, raita, curry, etc. Because of its safety as an edible plant, the present results on thrombolytic activity could be promising for its dietary inclusion for persons who have suffered or are predisposed to CVD.

CONCLUSION

Leaves of C. album have been shown to possess 39.70±0.99% in vitro clot lysis activity with moderate positive correlation with TC, TG and Non-HDL-C levels. The thrombolytic activity may be due to the presence of the two major phytochemical groups such as phenols and flavonoids. However, in vivo studies with a larger number of subjects along with quantitative estimation of bioactive molecules are required to establish the thrombolytic potential of C. album.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT

The present study first time reveals the in vitro thrombolytic potential of leaves of Chenopodium album L. It will motivate the researchers to find out the anti-thrombotic molecules from the plant and help in a recommendation of this edible plant for the prevention of CVD.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Authors are thankful to the Botanical Survey of India, Arid Zone Regional Centre, Jodhpur, Rajasthan for authentication of the plant and also to Shri Pratap Kaushik, RNT Medical College, Udaipur, Rajasthan for helping in statistical analysis.

REFERENCES

- Wendelboe, A.M. and G.E. Raskob, 2016. Global burden of thrombosis: Epidemiologic aspects. Circ. Res., 118: 1340-1347.

- Soppert, J., M. Lehrke, N. Marx, J. Jankowski and H. Noels, 2020. Lipoproteins and lipids in cardiovascular disease: From mechanistic insights to therapeutic targeting. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev., 159: 4-33.

- Guguloth, S.K., N. Malothu, U. Kulandaivelu, K.G.S.N. Rao, A.R. Areti and S. Noothi, 2021. Phytochemical investigation and in vitro thrombolytic activity of Terminalia pallida Brandis leaves. Res. J. Pharm. Technol., 14: 879-882.

- Collen, D., 1990. Coronary thrombolysis: Streptokinase or recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator? Ann. Intern. Med., 112: 529-538.

- Hossain, S., B. Sarkar, M.N.I. Prottoy, Y. Araf, M.A. Taniya and M. Asad Ullah, 2019. Thrombolytic activity, drug likeness property and ADME/T analysis of isolated phytochemicals from ginger (Zingiber officinale) using in silico approaches. Mod. Res. Inflammation, 8: 29-43.

- Prasad, S., R.S. Kashyap, J.Y. Deopujari, H.J. Purohit, G.M. Taori and H.F. Daginawala, 2006. Development of an in vitro model to study clot lysis activity of thrombolytic drugs. Thromb. J., 4: 14.

- Tiagi, Y.D. and N.C. Aery, 2007. Flora of Rajasthan: South & South-East Region. Himanshu Publications, New Delhi, India, ISBN: 9788179061572, Pages: 726.

- Jain, V. and S.K. Jain, 2017. Dictionary of Local-Botanical Names in Indian Folk Life. 1st Edn., Scientific Publishers, Jodhpur, ISBN: 978-93-83692-51-4, Pages: 329.

- Saini, S. and K.K. Saini, 2020. Chenopodium album Linn: An outlook on weed cum nutritional vegetable along with medicinal properties. Emergent Life Sci. Res., 6: 28-33.

- Jain, S.K., 1991. Dictionary of Indian Folk Medicine and Ethnobotany. Deep Publication, New Delhi, India, ISBN-13: 978-8185622002, Pages: 311.

- Jain, V. and S.K. Jain, 2016. Compendium of Indian Folk Medicine and Ethnobotany (1991-2015). Deep Publications, New Delhi, ISBN: 978-9380702100, Pages: 542.

- Bhutya, R.K., 2011. Ayurvedic Medicinal Plants of India. Scientific Publishers, India, ISBN: 9789387991477, Pages: 1000.

- Chamkhi, I. , S. Charfi, N. El Hachlafi, H. Mechchate and F.E. Guaouguaou et al., 2022. Genetic diversity, antimicrobial, nutritional, and phytochemical properties of Chenopodium album: A comprehensive review. Food Res. Int., 154: 110979.

- Choudhary, N., K.S. Prabhu, S.B. Prasad, A. Singh, U.C. Agarhari and A. Suttee, 2020. Phytochemistry and pharmacological exploration of Chenopodium album: Current and future perspectives. Res. J. Pharm. Technol., 13: 3933-3940.

- Verma, S.K., V. Jain and S.S. Katewa, 2023. Effect of cinnamon (Cinnamommum verum J. Presl.) on blood lipids, fibrinogen, fibrinolysis, and total antioxidant status in patients with ischemic heart disease. Acta Sci. Med. Sci., 7: 104-111.

- Kunwar, B., V. Jain and S.K. Verma, 2022. In vitro thrombolytic activity of Moringa oleifera. Nusantara Biosci., 14: 63-69.

- Edeoga, H.O., D.E. Okwu and B.O. Mbaebie, 2005. Phytochemical constituents of some Nigerian medicinal plants. Afr. J. Biotechnol., 4: 685-688.

- Anandjiwala, S., H. Srinivasa, J. Kalola and M. Rajani, 2007. Free radical scavenging activity of Bergia suffruticosa (Delile) Fenzl. J. Nat. Med., 61: 59-62.

- Prasad, S., R.S. Kashyap, J.Y. Deopujari, H.J. Purohit, G.M. Taori and H.F. Daginawala, 2007. Effect of Fagonia arabica (Dhamasa) on in vitro thrombolysis. BMC Complementary Altern. Med., 7: 36.

- Allain, C.C., L.S. Poon, C.S.G. Chan, W. Richmond and P.C. Fu, 1974. Enzymatic determination of total serum cholesterol. Clin. Chem., 20: 470-475.

- Fossati, P. and L. Prencipe, 1982. Serum triglycerides determined colorimetrically with an enzyme that produces hydrogen peroxide. Clin. Chem., 28: 2077-2080.

- Friedewald, W.T., R.I. Levy and D.S. Fredrickson, 1972. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin. Chem., 18: 499-502.

- Puri, R., S.E. Nissen, M. Shao, M.B. Elshazly and Y. Kataoka et al., 2016. Non-HDL cholesterol and triglycerides: Implications for coronary atheroma progression and clinical events. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol., 36: 2220-2228.

- Harun-Or-Rashid, M., M.M. Akter, Jalal Uddin, S. Islam and M. Rahman et al., 2023. Antioxidant, cytotoxic, antibacterial and thrombolytic activities of Centella asiatica L.: possible role of phenolics and flavonoids. Clin. Phytosci., 9: 1.

- Mackman, N., 2008. Triggers, targets and treatments for thrombosis. Nature, 451: 914-918.

- Al-Qahtani, J., A. Abbasi, H.Y. Aati, A. Al-Taweel and A. Al-Abdali et al., 2023. Phytochemical, antimicrobial, antidiabetic, thrombolytic, anticancer activities, and in silico studies of Ficus palmata Forssk. Arabian J. Chem., 16: 104455.

- Siddika, A., A. Sultana, L. Khatun and S.M.M. Parvez, 2021. Evaluation of antioxidant, cytotoxic, thrombolytic and antimicrobial potentials of stem and root parts of Phyllanthus fraternus G.L. webster grown in Northern part of Bangladesh. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem., 10: 1-8.

- Patel, S., 2016. Plant-derived cardiac glycosides: Role in heart ailments and cancer management. Biomed. Pharmacother., 84: 1036-1041.

- Ciumărnean, L., M.V. Milaciu, O. Runcan, Ș.C. Vesa and A.L. Răchișan et al., 2020. The effects of flavonoids in cardiovascular diseases. Molecules, 25: 4320.

- Lutz, M., E. Fuentes, F. Ávila, M. Alarcón and I. Palomo, 2019. Roles of phenolic compounds in the reduction of risk factors of cardiovascular diseases. Molecules, 24: 366.

- Pandey, S. and R.K. Gupta, 2014. Screening of nutritional, phytochemical, antioxidant and antibacterial activity of Chenopodium album (Bathua). J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem., 3: 1-9.

- Das, A. and M.K. Borthakur, 2022. Chenopodium album Linn.: A review on various pharmacological activities. Uttar Pradesh J. Zool., 43: 9-14.

- El-Rokiek, K.G., S.A.S. El-Din, A.N. Shehata and S.A.M. El-Sawi, 2016. A study on controlling Setaria viridis and Corchorus olitorius associated with Phaseolus vulgaris growth using natural extracts of Chenopodium album. J. Plant Protect. Res., 56: 186-192.

- Lamponi, S., 2021. Potential use of plants and their extracts in the treatment of coagulation disorders in COVID-19 disease: A narrative review. Longhua Chin. Med., 4.

- Cutillo, F., M. DellaGreca, M. Gionti, L. Previtera and A. Zarrelli, 2006. Phenols and lignans from Chenopodium album. Phytochem. Anal., 17: 344-349.

- Amodeo, V., M. Marrelli, V. Pontieri, R. Cassano, S. Trombino, F. Conforti and G. Statti, 2019. Chenopodium album L. and Sisymbrium officinale (L.) Scop.: Phytochemical content and in vitro antioxidant and anti-inflammatory potential. Plants, 8: 505.

- Poonia, A. and A. Upadhayay, 2015. Chenopodium album Linn: Review of nutritive value and biological properties. J. Food Sci. Technol., 52: 3977-3985.

- Ravnskov, U., M. de Lorgeril, M. Kendrick and D.M. Diamond, 2022. Importance of coagulation factors as critical components of premature cardiovascular disease in familial hypercholesterolemia. Int. J. Mol. Sci., 23: 9146.

- Singh, P., Y.S. Hare and U.K. Patil, 2010. Assessment of hypolipidemic potential of Chenopodium album Linn on triton induced hyperlipidemic rats. Res. J. Pharm. Technol., 3: 187-192.

How to Cite this paper?

APA-7 Style

Kunwar,

B., Jain,

V., Verma,

S.K. (2023). Phytochemical Screening and in vitro Evaluation of the Thrombolytic Activity of Chenopodium album L. Leaves. Pharmacologia, 14(1), 21-28. https://doi.org/10.17311/pharmacologia.2023.21.28

ACS Style

Kunwar,

B.; Jain,

V.; Verma,

S.K. Phytochemical Screening and in vitro Evaluation of the Thrombolytic Activity of Chenopodium album L. Leaves. Pharmacologia 2023, 14, 21-28. https://doi.org/10.17311/pharmacologia.2023.21.28

AMA Style

Kunwar

B, Jain

V, Verma

SK. Phytochemical Screening and in vitro Evaluation of the Thrombolytic Activity of Chenopodium album L. Leaves. Pharmacologia. 2023; 14(1): 21-28. https://doi.org/10.17311/pharmacologia.2023.21.28

Chicago/Turabian Style

Kunwar, Bhavika, Vartika Jain, and Surendra K. Verma.

2023. "Phytochemical Screening and in vitro Evaluation of the Thrombolytic Activity of Chenopodium album L. Leaves" Pharmacologia 14, no. 1: 21-28. https://doi.org/10.17311/pharmacologia.2023.21.28

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.